OAKLAND — There was hardly room to stand, but Cindi Beam rose to hug every well-wisher who stopped by to say their lives were changed by Coach John Beam.

A former Skyline High School tight end donning a letterman jacket wept as his mother whispered into Cindi’s ear. The coach’s wife returned a deep gaze into the woman’s eyes, echoing the kind of direct eye contact that John was known to offer anyone seeking his guidance when he served as the high school’s legendary football coach.

Beam was fatally shot last month at Laney College’s Field House, the athletics facility where he held court and shaped generations of young men.

The scene at Everett and Jones Barbecue, where on Friday the sports icon was memorialized, reflected a different town. This was an Oakland that Beam knew well — where sports forges the kind of lifelong community bonds that overcome any undercurrent of tragedy.

“I’m thankful for what your husband has done for my life story,” Damon Owens, a 1991 alum of Skyline High, told Cindi on the microphone. He was among a packed sea of red Skyline jackets, former student athletes who greeted each other jovially during an otherwise emotional celebration of a man who had believed in their success.

Beam, who received national recognition after his appearance in the Netflix series “Last Chance U,” is among the highest-profile Bay Area residents to be killed in recent memory — a shooting that sent shockwaves through the city’s tight-knit sports community.

Skyline High leaders had already figured they would rename the football field after Beam. By next season, the change will become official. Beam turned the program into a powerhouse amid a 40-plus year career in Oakland. He left in 2004 to begin coaching at Laney, where he remained as athletics director before his death last month.

He befriended and mentored the standout young athletes who came up through the city, transcending sports to become a community leader who defined Oakland’s success by more than just sports.

Deon Strother, a Skyline alum who played a season in the NFL, recalled fumbling the ball four times in the homecoming game after being named the school’s “king.” Beam, who saw the kid had fought hard, continued to put the ball in the running back’s hands.

“Being older now,” said Strother, now in his 50s, “I’m able to see — I needed that validation. I was the one in my family that had to do everything right. And I thought people’s love and affirmation was based on my performance. So for him to continue giving me ball after that, it showed that he really loved me and he believed in me.”

Beam is survived by Cindi and daughters Monica and Sonjha. The family declined to comment during and after the memorial.

But speaker after speaker rose to remember the encouragement Beam gave them to influence their life path. Shalon Cortez described how the coach said she could do “whatever you want.”

“I ran track, I played basketball, I was on the swim team and I even was an editor of the school yearbook,” said Cortez, who was diagnosed at a young age with autism. “That type of person in your life is the reason why a lot of us have that grit we need to get past obstacles.”

The testimony made an impact on Jamaal Kizziee, who served as Skyline’s football coach in the late 2000s after Beam left for Laney. He noted that his predecessor had influenced women athletes as much as he did the men who suited up for his football squads.

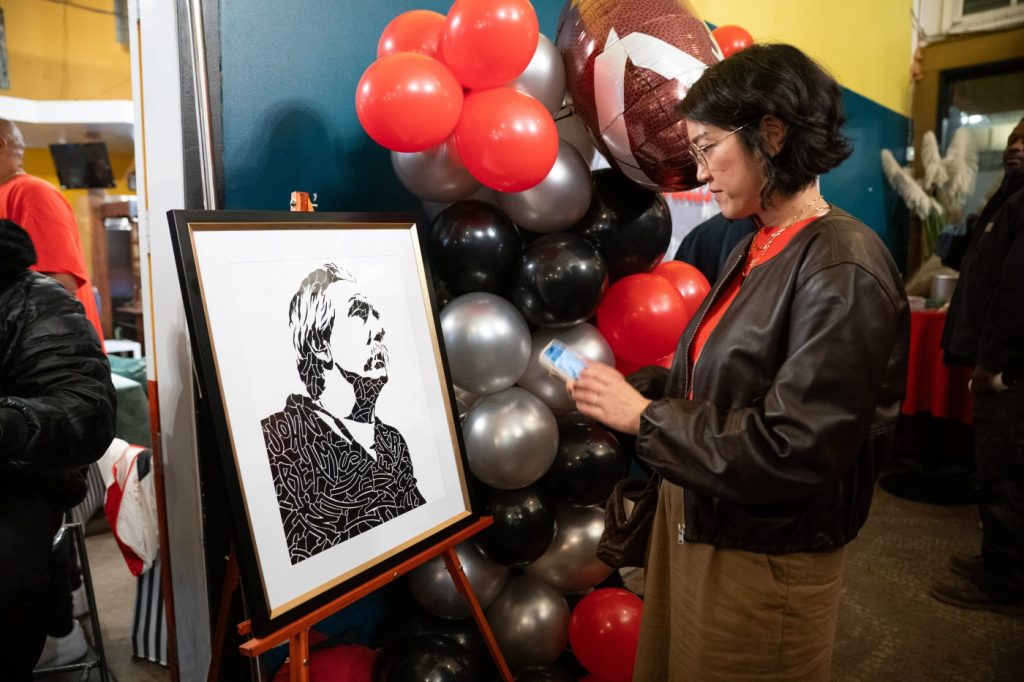

A portrait of Beam, with his signature mustache and eyes gleaming with wisdom, hung in the back of the stage. Beyond the hundreds packed into Everett and Jones, a poster board leaned against a wall saw a woman scrawling, “Love you for life — thank you for everything.”

A few doors down, the Merchants’ Saloon bar sat quiet. Beam’s coaching staff had been known to drink there after long days of training camp and practices. Patrons shuffled out of the nearby restaurant into cars.

“He touched lives all over the place,” Kizziee said. “We all got brought together through that sense of care. That’s Oakland.”

Shomik Mukherjee is a reporter covering Oakland. Call or text him at 510-905-5495 or email him at shomik@bayareanewsgroup.com.